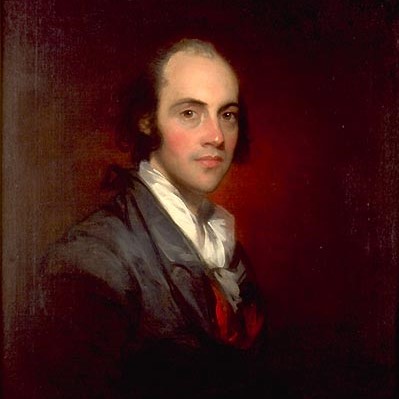

Burr’s Missing Puzzle Piece

Aaron Burr is an underrated figure in United States history, not necessarily because he was a much better person than most people believe (that much is open to debate) but because he is far more interesting than might at first be imagined. Though some people may be aware that Burr was an orphan, not many are aware that his next two guardians died quickly as well; though some people may be aware that Burr was controversial in politics, not many are aware that he championed women’s rights; and though some people may be aware of Burr’s reputation as an out of control ladies’ man, not many are aware that Burr also had several romantic and perhaps sexual relationships with men.

Early Years

Aaron Burr was born on February sixth, 1756, to Esther Edwards and Aaron Burr Sr.¹ A little over a year after Burr’s birth, his father died, and his mother died just months after that.² Burr and his sister would go through several guardians before finally going to live with their maternal uncle, Timothy Edwards. At that point Burr’s life finally began to smooth out, and Burr had a fairly normal childhood culminating in his entering Princeton at the age of thirteen.³

It was likely at Princeton that Burr met Robert Troup, who attended briefly before transferring to King’s College (now Columbia University).⁴ Troup, the son of privateer Robert Troup Sr. and his wife Elinor Bisset, was by then also an orphan, and he and Burr became close friends.⁵ Burr and Troup continued to correspond after they both joined the Continental Army, and as the war was winding to a close Troup suggested that they finish their law studies together; Burr tentatively agreed.⁶ In several of his subsequent letters Troup told Burr how happy he was about the prospect of them living together, in one letter telling him “If we once get together I hope we shall not soon be parted. It would afford me the greatest satisfaction to live with you during life,” in another confessing “My future prosperity in life depends in a great degree Burr you may imagine on my living and studying with you.”⁶ Troup also told Burr that the man they would be studying under had several unmarried daughters, then asked “But why should we connect ourselves with any of them, so as to interrupt our studies?”⁷

They had initially planned to study under a different lawyer, and when Troup decided they should instead study under William Patterson Burr wavered, and he ended up spending some time in Connecticut studying under their original choice.⁸ Eventually however Burr did decide to move to New Jersey with Troup. Assuring Troup they would soon be together, Burr instructed him “Hold yourself aloof from all engagements, even of the heart.” (Emphasis original)⁹

Courtship and Married Life

After his time at Princeton and before his time living with Troup, Burr served in the Continental Army. Burr served first under Benedict Arnold and then under General Richard Montgomery, until the General fell in battle not long after.¹⁰ Burr served a trial period as an unofficial aide de camp to George Washington, but he and Washington immediately disliked each other, and Burr quit just one week later.¹¹ Burr then became an aide de camp to General Israel Putnam, and served in that capacity till health problems (mostly as a result of heatstroke suffered during the Battle of Monmouth) forced him to resign.¹²

After Monmouth, but before his resignation, Burr was sent on a mission behind Loyalist lines. That was when he met Theodosia Bartow Prevost.¹³ When his regiment later found themselves in New Jersey, Burr became a frequent guest at Prevost’s house, which was the social center of town. Though Prevost was married to a British officer, at that time her husband, John Mark Prevost, was not directly a part of the war, as he was serving in the Carribean, so she freely associated with Patriots and Loyalists alike.¹⁴ Prevost was always surrounded by available young men, including Robert Troup, and they all initially appeared to be on the same footing with her; friends, perhaps admirers, but none of them her lover.¹⁵ Troup’s letters to Burr from that time seem to suggest that Troup thought they were both simply Prevost’s friends, and it is possible he did not know that Burr and Prevost’s relationship was beginning to take on a different tone.

Though by 1779 John Prevost was becoming a part of the war, Burr spent more and more time with Theodosia Prevost, who even began to become friends with his sister. In 1781 news reached Burr that John Prevost had died of disease while once again in the Carribean, and Burr lost little time in proposing. Prevost and Burr were married July second of 1782, and their first child, a daughter named Theodosia, was born June twenty-first, 1783. The couple later had two boys who were stillborn, and a second daughter, Sally Burr, who died at age three.¹⁶

Most accounts of Burr and Prevost’s relationship agree that it was a good one. They were both admirers of Mary Wolstonecraft, essentially making them feminists, and so they mutually agreed that their relationship would be an equal partnership based on love. Prevost was Burr’s best friend and his most useful political advisor; it seems likely that he really did love her.¹⁷

Still, their relationship was far from perfect. There were plenty of rumors that Burr was unfaithful, the validity of which has been debated ever since. A recent discovery has proven conclusively that Burr did have at least one relationship with another woman during his marriage; DNA testing on the descendant of a man named John Pierre proved that Pierre was Burr’s son with his wife’s slave, Mary Emmons.¹⁸

Emmons had been sold into slavery while a child in India, and she was brought to America by John Mark Prevost. She continued to serve in the Prevost household after John Mark Prevost died, and may have first met Burr while he was courting Prevost.¹⁹ Near the end of his marriage to Prevost (which ended with her death of pancreatic cancer) Burr was elected to the Senate. Burr found a place to live in the capitol when he needed it, and he took Emmons with him. While Burr’s wife and daughter lived in their home in New York, in Philadelphia Burr and Emmons had two children, John Pierre and Louisa Charlotte.²⁰ Emmons later died, and Burr was there to help their children whenever they needed it.²¹ Theodosia Jr. apparently learned of her half siblings at some point, likely years after her mother’s death, and she and Louisa became close.²² As Emmons was Burr’s slave, and as it was only recently that Burr’s relationship with Emmons was confirmed as fact, it is currently impossible to say whether their relationship was consensual. Hopefully in the future historians will have more information to clarify this.

European Adventures

If Burr recovered at all from the deaths of his wife and his long time lover, this was but a brief reprieve before the downward spiral Burr was about to begin. The span of a few years brought the duel in which Burr killed Alexander Hamilton and then treason charges for an alleged attempt to take over Mexico and part of the United states. Though Burr never faced prosecution for Hamilton’s death and was acquitted of the treason charges, his reputation was utterly destroyed.

With no more prospects in the United States, Burr left for Europe sometime in 1808.²³ Burr wanted to share his European adventures with his daughter, Thedosia, with whom he had always been very close, so he wrote her an impressive amount of letters, in addition to writing a journal he intended for her to eventually read. Because of this, it is during this period of his life that his romantic and even sexual endeavors are perhaps best documented. Included in these are a plethora of references to attraction to males. Notable amongst these references is one in which he tells Theodosia he had “been amused for an hour with a very handsome young Dane.” He follows this up with “Don’t smile. It is a male!”²⁴ If by “been amused” Burr had meant anything other than flirting, it would not make much sense for him to make such a big deal out of the “Dane” being male; he could simply have mentioned for instance that he had spent an hour joking with a young man. Instead he does not immediately reveal the person’s gender, and when he does, expects Theodosia to react to it. Interestingly, Burr thinks this revelation is going to make Theodosia smile, which suggests that Theodosia not only knew about her father’s same-gender attraction, but that she found it either amusing or slightly endearing.

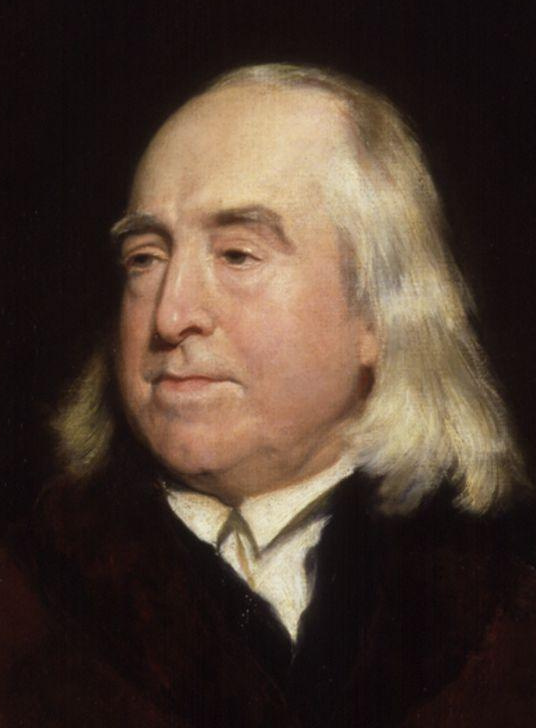

Not long after he began living in London, England, Burr met English philosopher and political theorist Jeremy Bentham.²⁵ The two instantly became friends, and Bentham invited Burr to live with him, which Burr would do on and off from December of 1808 until Burr returned to the United States in 1812.²⁶ Burr and Bentham were inseparable. In one letter to his daughter Burr explains that he was “now writing in Mr. B’s room, and by his side. He wills it so, insiting that there is a sort of social intercouse in sitting near, and looking now and then at each other, though we are separately and ever so intensely employed. It is certainly so.”²⁷ Burr’s letters and journal entries include at least thirty mentions of spending time with Bentham reading together, having dinner together, discussing philosophy or Theodosia, and more. Bentham was instantly taken with Theodosia; Burr encouraged her to write to Bentham and even tried to send her a bust of him.²⁸

Very quickly a new element of their mutual attachment emerged. Just a month after they met, while briefly separated by distance, Burr wrote to Bentham “Every hour of every day I have conversed with you. In solitude, in company, at dinners, routes, balls -during tho discussion of things the most remote from all association with you, you appear and look me in the face…”²⁹ Romantic moments like these would reappear from time to time in their correspondence, with Bentham assuring Burr in 1811 “I do believe that, of the regard you have all along professed for me, no inconsiderable part is true.”³⁰

In order to view all of this in the right light, it is important to acknowledge that Jeremy Bentham was almost certainly gay. In 1978 the Journal of Homosexuality, a peer reviewed journal that covers a wide range of LGBTQIA+ topics, published the essay “Offenses Against Oneself”. Bentham wrote this essay in 1785, but he never published it for fear of possible consequences.³¹ In this essay Bentham argues that, though homosexuality may not necessairly be a good thing (he portrays it along the lines of a bad habit or vice) it does not affect anyone but the people who willingly engage in same-gender relations, so it cannot be reasonably criminalized.

Even before the twentieth century publication of “Offenses” Bentham’s sexuality was not completely a secret; it seems that while Bentham was alive, it may have been somewhat common knowledge amongst those who knew him. At one point in his journal Burr mentions that he had an interesting conversation with some men concerning Bentham. Though he tells Theodosia that he cannot put down on paper all that was said, he tells her “A few hints may serve as memoranda. “I would rather our friend Bentham should write on legislation than on morals!” Holy Father, if ever one of thy creates was endued with benevolence without alloy ———–,”.” (Burr ended the sentence with a dash.) Burr goes on to say that one of the men in the conversation, though he has great respect for Bentham’s intellectual merits, believes Bentham will go to hell.⁺ Burr writes of that conversation somewhat sarcastically, but earlier in the diary, with a more sober tone, Burr says that he and Bentham had privately discussed same-sex relationships. Burr tells Theodosia that he spent the evening with Bentham, and that they “conversed of tattooing, how to be made useful; infanticide; of crimes against Nature, &c., &c.”⁺⁺ Though “crimes against nature” may sound vague now, during the eighteenth century it was often used as a euphism for same-sex relations.

Attached as he may have been to Bentham, just like during his marriage to Theodosia Prevost Burr was not monogamous. His correspondence during his time in Europe includes several love letters to women whose names are not known.³² Additionally, Burr later adopted two boys who were rumored to have been Burr’s biological sons with women he met in Europe.³³

Later Years

Burr returned to America in 1812, and resumed his law career. Though Burr was connected with a political plot in Latin America and an economic scheme in South America, the rest of his life would be fairly quiet.³⁴ Theodosia’s son had died while Burr was in Europe, and Theodosia herself died in 1813.³⁵ Burr did marry a second time, but his wife, Eliza Jumel, divorced him for exploiting her fortune and for adultery.³⁶ Her claim certainly shows that Burr’s love life had not slowed down any (though he was by then in his seventies) as does the fact that, in a will written a year before his death, he claimed two daughters by two different mothers.³⁷

While Robert Troup expressed romantic affection for Aaron Burr, it is unclear if Burr returned those feelings, and so Burr’s relationship with Troup may not prove anything about Burr’s sexual or romantic orientation. In the journal he kept during his years in Europe, however, Burr does set a pattern of at least noticing and flirting with attractive men. Even more revealing is Burr’s relationship with Jeremy Bentham. Burr’s lengthy correspondence with Bentham does include moments that feel romantic, and these moments take on even greater significance when it is considered that Bentham’s very early advocacy for gay rights suggests he was most likely gay. Just as significant as his relationship with Bentham is Burr’s relationship with his first wife, Theodosia Bartow Prevost. Burr does seem to have married Prevost for love, in part because it does not seem like she would have agreed to marry him if she suspected he were using her. Thus Burr was most likely bisexual. As Aaron Burr is so often shrouded in mystery, this one piece of the puzzle, however small it may seem, gets us a little bit closer to the full picture.

Note on art credits: I was unable to find the names of the artists of the painting I included of Burr and Prevost. If you know who they are, please let me know in the comments so I may credit them!

If you value what I do here, please consider becoming my Patron! 18th Century Pride is creating LGBT+ History Content | Patreon

- https://www.britannica.com/biography/Aaron-Burr, “Aaron Burr”, Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica

- The Papers of Aaron Burr, Volume One, “Historical Introduction”, 1IV-1V, Mary Jo-Kline

- Ibid., 1IV, 1X

- http://exhibitions.nysm.nysed.gov/albany/bios/t/rotroup.html, “Robert Troup”, Stefan Bielinski

- https://oxfordindex.oup.com/view/10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.0200318, “Troup, Robert”, Wendell Tripp

- Robert Troup to Aaron Burr, 16 May, 1780

- Robert Troup to Aaron Burr, 16 Jan., 1780

- See #2, 1XI

- Aaron Burr to Robert Troup, 15 May, 1780

- See #2, 1XXII

- George Washington’s Indispensable Men, Arthur S. Lefkowitz, 58

- See #2, 1XIV

- Ibid., 1XIII

- Fallen Founder, Nancy Isenberg

- Ibid.

- http://aaronburrassociation.org/tragedies.htm, “The Tragedies in Aaron Burr’s Life”, Aaron Burr Association (It should be noted that this list is slightly out of date, and does not take into account recent discoveries such as Burr’s relationship with Mary Emmons.)

- See #14

- “Aaron Burr — villain of ‘Hamilton’ — had a secret family of color, new research shows”, Hannah Natanson

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- See #1

- The Private Journal of Aaron Burr, Aaron Burr, 40

- Aaron Burr to Theodosia Burr Alston, September 9, 1809

- Ibid.

- Aaron Burr to Theodosia Burr Alston, Nov. 21, 1808

- See #25

- Aaron Burr to Jeremy Bentham, January 23, 1809

- Jeremy Bentham to Aaron Burr, January 18, 1811

- http://www.columbia.edu/cu/lweb/eresources/exhibitions/sw25/bentham/index.html, “Offenses Against One’s Self”, Louis Crompton (editor, wrote background information)

- For one example, see Aaron Burr to “Anonymous Lady”, March 28, 1811

- https://books.google.com/books?id=RAGKCgAAQBAJ&pg=PP168#v=onepage&q&f=false, The Remarkable Rise of Eliza Jumel, Margret Oppenhiemer

- See #2, 1XVIII

- Ibid.

- See #1

- See #14

+ The Private Journal of Aaron Burr, Aaron Burr, 43-44

++Ibid., 12

An Anonymous Person

Wow, this is really great! I never knew Burr was bisexual. I’m using this website for an essay I’m writing for school, and it’s very helpful. Thanks so much!

Hex

Hmm well we don’t have an exact answer for him and Robert Troup. We do have a sort of confirmed answer for Aaron Burr and Jonathan Bellamy. Although he wasn’t mentioned here, Jonathan Bellamy was another man who Aaron Burr met during his college years. Bellamy went to Yale, and him and Burr were also close friends. Basically what confirms this is the letters between these two men. Jonathan would usually call Burr ‘My Dearest Soldier’ in his letters to Aaron while Aaron was in the war. So this does sort of confirm ATLEAST one male lover for Aaron Burr.