The Hamilton-Laurens Letters

Alexander Hamilton and John Laurens met when Laurens joined George Washington’s military family, of which Hamilton was already a part, in August of 1777.¹ Though they came from different backgrounds, the two men had a lot in common, and they quickly became the best of friends. Indeed, years later many veterans of the Revolution would remember Hamilton and Laurens as an inseparable pair. But was the powerful bond they formed platonic, or did Hamilton and Laurens fall in love? To answer this question, many turn to the roughly two dozen surviving letters that passed between Hamilton and Laurens. Many historians have argued that these letters are not good enough evidence to say what kind of relationship Hamilton and Laurens had, but the letters constitute the clearest insight we have into how the two soldiers interacted. So what can we learn from the Hamilton-Laurens letters? Do they provide proof of a powerful love story, or are they just an example of how men formed friendships in the eighteenth century?

Early Letters

The first surviving letter, written by Laurens, is from almost a year and a half after he and Hamilton first met. The content of the letter concerns the slander of Washington spread by their shared enemy Charles Lee, slander which would eventually lead Laurens to fight a duel with Lee, with Hamilton as his second. For the purpose of evaluating Hamilton and Laurens’s realtionship, however, the most interesting part of the letter is not the content but the way in which Laurens signs it. Laurens ends his letter “Adieu, my dear boy.”² Hamilton was the only man Laurens ever addressed as “my dear boy.” The only thing similar to this in Laurens’s writings is “my dear girl,” the closing Laurens reserved exclusively for his wife.³

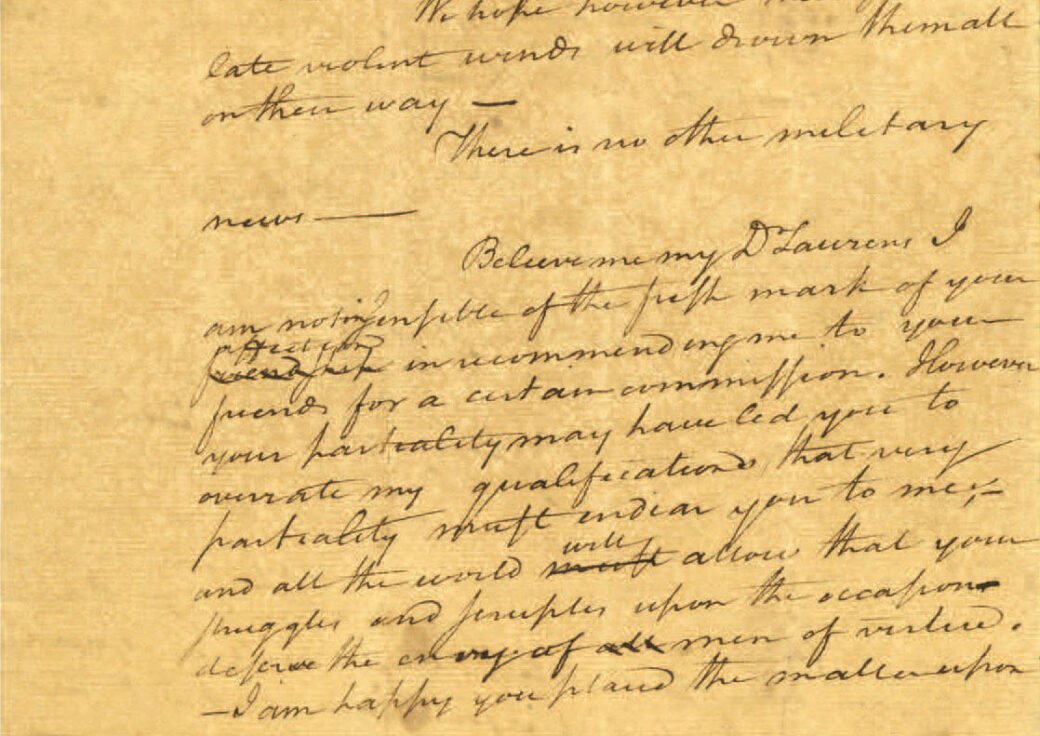

The next letter we have is from Hamilton. In this April 1779 letter, Hamilton tells Laurens: “Cold in my professions, warm in ⟨my⟩ friendships, I wish, my Dear Laurens, it m⟨ight⟩ be in my power, by action rather than words, ⟨to⟩ convince you that I love you….You know the opinion I entertain of mankind, and how much it is my desire to preserve myself free from particular attachments, and to keep my happiness independent of the caprice of others. You sh⟨ould⟩ not have taken advantage of my sensibility to ste⟨al⟩ into my affections without my consent.”⁴ This letter has often been disregarded as evidence that Hamilton loved Laurens romantically because the eighteenth century had such different standards for what level of affection was normal between male friends. While nowadays it would be surprising for male friends to say “I love you,” that was far from true during Hamilton’s time. One thing that should be considered however is the weight these words would have had for Hamilton. After a traumatic childhood, forming emotional attachments was apparently hard for Hamilton. Telling Laurens that he does not form bonds easily, but that he has formed a bond with him, is not something Hamilton would have done casually or lightly. Indeed, it is not something Hamilton says in letters to any other friend, or any other person at all, with the possible exception of his wife.

There are two more things that stand out in that letter. One of them is the one and only time that Hamilton mentions Laurens’s family. During his time studying law in England, Laurens had what seems to have been intended as a brief affair with his friend Martha Manning. The affair left Manning pregnant, and during her fifth or sixth month they eloped. Not long after that Laurens left for America to join the war effort, and he never saw Manning again. In this letter Hamilton tells Laurens, “I anticipate by sympathy the pleasure you must feel from the sweet converse of your dearer self in the inclosed letters. I hope they may be recent. They were brought out of New York by General Thompson delivered to him there by a Mrs. Moore not long from England, soi-disante parente de Madame votre épouse. She speaks of a daughter of yours, well when she left England, perhaps ⟨– – –⟩.” Readers often conclude that it was by reading that enclosed letter that Hamilton first learned Laurens was married. This may or may not be true. While it is possible that “I anticipate by sympathy the pleasure you must feel from the sweet converse of your dearer self in the inclosed letters,” could have been sarcasm, he follows this up with the perfectly normal and casual “I hope they may be recent.” Either way, his reference to Frances Laurens as “a daughter of yours,” could suggest that even if Hamilton knew Laurens was married, he did not know about Laurens’s daughter.

The last significant thing about this letter is the portion in which Hamilton asks Laurens to find him a wife. It is clear that he is not serious; he says so himself at the end of the letter, and his entire description of the advertisement Laurens should publish to find him a wife is done in a joking tone. Often overlooked however is the flirtatious tone of this passage, and the possibility that Hamilton was flirting with Laurens. For instance, at one point, while instructing Laurens how to describe Hamilton in the ad, Hamilton reminds him, “…mind you do justice to the length of my nose and don’t forget, that I ⟨– – – – –⟩.” The next few words were obliterated by some later editor, perhaps Hamilton’s son John Church Hamilton who prepared his father’s papers for publication after Hamilton’s death. “Nose” in this case is eighteenth century slang for penis. It is entirely possible, of course, that all of this is just bawdy humor between friends, but the possibility that Hamilton was flirting with Laurens is worth considering. LGBT historian Rictor Norton has suggested that Hamilton put in this section of the letter just to see how Laurens would react to the idea of Hamilton getting married.⁵ With Laurens’s hidden family on his mind, Hamilton may have wondered if Laurens wished their relationship could be just the two of them, or if Laurens accepted that they would both eventually be married with families.

Despite how much attention that letter gets, Hamilton’s more revealing language to Laurens might be in his more casual letters. In a later letter, while talking about a political stance Laurens’s father had taken, Hamilton writes, “I mention this matter to you, my Dr., because your good father…”⁶ Hamilton used the word “dear” (which he abbreviated “Dr.”) like this in many of his letters to Laurens, and it is highly significant. As I discussed earlier, it can be hard to tell when an eighteenth century man is just using the then-accepted amount of affection for a male friend versus being romantic. One thing that is for sure, however, is that using dear as an adjective was seen as very different than using it as a noun. This was originally pointed out to me by the blog John-Laurens on Tumblr, and as that blog points out, this phenomenon is best exemplified in Hamilton’s later correspondence with his sister-in-law, Angelica Church. In one letter Church referred to Hamilton, whether accidentally or on purpose, as “my dear, Sir…”⁷ Hamilton noticed this and commented on it in his response, telling her, “There was a most critical comma [sic] in your last letter. It is my interest that it should have been designed; but I presume it was accidental. Unriddle this if you can. The proof that you do it rightly may be given by the omission or repetition of the same mistake in your next.” He proceeded to sign that letter “Adieu ma chere, soeur.”⁸ [My dear, sister.] Hamilton thought Church might be flirting with him because by adding that comma she changed dear from an adjective to a noun; she called him “my dear” instead of just describing him as someone who was dear to her. When talking to John Laurens, Hamilton used “dear” the same way.⁹

In his next letter after Hamilton’s letter where he called Laurens “Dr.,” Laurens tells Hamilton, “Ternant [a fellow soldier] will relate to you how many violent struggles I have had between duty and inclination—how much my heart was with you, while I appeared to be most actively employed here.”¹⁰ This and other language Laurens used when writing to Hamilton may not seem very romantic, especially by eighteenth century standards. One thing that is important to keep in mind when reading Laurens’s letters, however, is that Laurens ordinarily did not include much emotion in his letters.¹¹ Rather than comparing Laurens’s letters to Hamilton to other writings of the day, we should compare them to other things Laurens wrote. When we do this it becomes evident that his relationship with Hamilton was different than other relationships in Laurens’s life.

Hamilton Gets Married

By this point Laurens had left Washington’s staff and returned to South Carolina so he could fight for his home state. Hamilton wrote to Laurens near the end of 1779 to tell him he was trying to get Washington to let him go south and join Laurens, but if this is true his request must have been denied.¹² It was around this time, in the winter of 1779/80, that Hamilton began looking for a wife. After the war Hamilton would be left with little money and nowhere to go. He had no connections to draw on for advancement in a world where connections were everything. By January, Hamilton had begun courting Elizabeth Schuyler.

By summer, Charleston had fallen to the British and Laurens was a prisoner of war.¹³ Hamilton wrote to him in June, to offer emotional support and to make an announcement. At the end of the letter Hamilton tells Laurens “Have you not heard that I am on the point of becoming a benedict? I confess my sins. I am guilty. Next fall completes my doom. I give up my liberty to Miss Schuyler. She is a good hearted girl who I am sure will never play the termagant; though not a genius she has good sense enough to be agreeable, and though not a beauty, she has fine black eyes—is rather handsome and has every other requisite of the exterior to make a lover happy. And believe me, I am lover in earnest, though I do not speak of the perfections of my Mistress in the enthusiasm of Chivalry.”¹⁴ It is a lukewarm description, and it marks the beginning of a tangle of deception, in which it is hard to say if Hamilton is lying to Schuyler about being attracted to her, or lying to Laurens about not being attracted to her. Perhaps in some way Hamilton was lying to both.

Hamilton and Laurens seem to have discussed Hamilton’s engagement, but we may never know what they said. Hamilton’s next letter to Laurens is missing, as is Laurens’s reply.¹⁵ After that Laurens seems to have stopped writing, as Hamilton’s next letter to him includes his annoyance that he has not received letters from Laurens in a while.¹⁶ Hamilton’s next letter after that is one of the most interesting in their entire correspondence, for the purpose of learning about Hamilton and Laurens’s relationship. Hamilton spends most of the letter attempting to comfort Laurens, whom Hamilton suspects may have fallen into depression during his time spent unable to take part in the war. At the end of the letter, however, Hamilton abandons the subject of Laurens’s captivity and begins to reassure him about something else. Hamilton tells Laurens: “In spite of Schuylers [sic] black eyes, I have still a part for the public and another for you; so your impatience to have me married is misplaced; a strange cure by the way, as if after matrimony I was to be less devoted than I am now.”¹⁷ There are many important things in this quote. First of all, Hamilton refers to the part of himself that loves Schuyler as the part of himself “for the public.” This would suggest that Hamilton’s love for Schuyler is for appearances, unlike the apparently more personal part of him that remains Laurens’s. Hamilton then reveals that Laurens desperately wanted him to get married, believing this would cure Hamilton of his devotion to Laurens. If Hamilton and Laurens were not lovers, it is hard to understand why Laurens believed Hamilton needed to be “cured” of their relationship. Laurens clearly believed that Hamilton’s attachment to him would get in the way of Hamilton’s happiness, a belief that does not make sense if one assumes they were friends. Surely friendship with an elite southern gentleman would only have proved an asset to Hamilton as his life went on?

Final Letters

A few months later, Hamilton and Schuyler were married, and around that same time Laurens ceased to be a prisoner and was sent to France as an assistant to Benjamin Franklin.¹⁸ Hamilton wrote to Laurens to give him advice on how best to work with the French Court, and it is at the end of this letter that we see the only instance of Hamilton sending Schuyler’s love in his closing.¹⁹ It is significant that Hamilton only does this once, and that he never asks Laurens to send Martha Manning his love. Reading any amount of eighteenth century correspondence will teach a reader that including love to and from wives was standard etiquette for men of the day, especially between friends. But Schuyler and Manning remained delicate topics in Hamilton and Laurens’s correspondence.

By the next time Hamilton and Laurens saw each other, at the Battle of Yorktown, Hamilton’s wife was pregnant. Whether they discussed this in person we do not know, but no mention of his impending fatherhood appears in Hamilton’s letters to Laurens. He may have mentioned his son Phillip later however, in two letters that we do not have. In Laurens’s first letter to Hamilton after Yorktown, Laurens mentions two letters from Hamilton, and it sounds like Hamilton talked about his newfound responsibilities as a husband and father. Apparently Hamilton felt that these responsibilities might mean he should not accept the appointment to Congress he had received. Laurens reacts with irritation, telling Hamilton: “Your private affairs cannot require such immediate and close attention; you speak like a pater familias surrounded with a numerous progeny.”²⁰ There are two important things here: the first is that Laurens seems highly annoyed by Hamilton discussing his family, although perhaps Laurens genuinely is annoyed that Hamilton is acting like he cannot serve his nation at all now that he has one baby. The second is that in Laurens’s reprimand he manages to avoid directly mentioning Schuyler or Phillip. As discussed above, this aversion to discussion of family is highly unusual for correspondence between two eighteenth century friends.

Laurens closed this letter “You know the unalterable sentiments of your affectionate Laurens.” This is the most affectionate closing Laurens ever wrote. It was also the last thing he ever wrote to Hamilton. Laurens was killed in a skirmish near Combahee River a month later, and he never received Hamilton’s last letter to him, a letter urging Laurens to come to Congress so they could “hand in hand” build the nation they had dreamed up together.²¹ Hamilton learned of Laurens’s death sometime around October.²² By all accounts the event changed Hamilton forever. He had opened his heart to Laurens in a way he never thought he could, and he never did it again. As historian Ron Chernow put it: “After the death of John Laurens, Hamilton shut off some compartment of his emotions and never reopened it.”²³

Many historians contend that the letters that passed between Alexander Hamilton and John Laurens are not enough proof to say that the two men had a romantic and possibly sexual relationship. Surely all male friends talked to each other this way in the seventeen hundreds? But Hamilton and Laurens’s correspondence is full of things the two men did, accidentally or on purpose, to differentiate their correspondence from the correspondence of male friends.

Readers who find the Hamilton-Laurens letters to be typical of friends in that time may not be going deep enough. Yes, it is a mistake to simply see the two men writing to each other with affection and assume it was a romantic relationship; affection between male friends of the day was expected. But it is also a mistake to see the affection, recognize that affection between men was normal, and go no further. There seem to be three particularly important things to keep in mind when reading correspondence. The first is that any correspondence should first be compared to other things written by the correspondents themselves, not by other people of the same era. Second, the things the correspondents do not talk about are just as revealing as those that they do. Thirdly, readers may just need to approach subjects like these with a more open mind. Historians sometimes overlook the most glaring clues in the attempt to see Alexander Hamilton and John Laurens as two heterosexual best friends. When we open our minds, dive more deeply than at first seems necessary, and evaluate each relationship individually for the people involved, we gain insight into worlds, some large and some very private, that otherwise remain closed.

Correction: When this article was originally uploaded, I claimed full credit for noticing the difference between “dear” used as a noun and as an adjective. Later I realized that I had read an article explaining this on the John-Laurens Tumblr blog before noticing the fact myself, and so it is rightly their discovery and not mine. I edited this article to include proper credit on 2/13/22.

- George Washington to John Laurens, 5 August 1777, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-10-02-0527

- John Laurens to Alexander Hamilton, 5 December 1778, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-01-02-0673

- Of him who promises much, much will be expected., Are there any letters we can view that show… (tumblr.com)

- Alexander Hamilton to John Laurens, April 1779, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-02-02-0100

- “Revolutionary Love,” Rictor Norton, Gay Love Letters through the Centuries: Alexander Hamilton (rictornorton.co.uk)

- Alexander Hamilton to John Laurens, 22 May 1779, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-02-02-0151

- Angelica Church to Alexander Hamilton, 2 October 1787, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-04-02-0144

- Alexander Hamilton to Angelica Church, 6 December 1787, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-04-02-0172

- Of him who promises much, much will be expected., thelittlelionofvalleyforge: The Importance of… (tumblr.com)

- John Laurens to Alexander Hamilton, 14 July 1779, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-02-02-0321

- See #3

- Alexander Hamilton to John Laurens, 8 January 1780, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-02-02-0568

- “Americans Suffer Worst Defeat of Revolution at Charleston”, Americans suffer worst defeat of revolution at Charleston – HISTORY

- Alexander Hamilton to John Laurens, 30 June 1780, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-02-02-0742

- Alexander Hamilton to John Laurens, 19 July 1780 (missing letter), https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-02-02-0768 and John Laurens to Alexander Hamilton, 8 September 1780 (missing letter), https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-02-02-0845

- Alexander Hamilton to John Laurens, 12 September 1780, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-02-02-0851

- Alexander Hamilton to John Laurens, 16 September 1780, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-02-02-0860

- John Laurens and the American Revolution, George Massey, 241

- Alexander Hamilton to John Laurens, 4 February 1781, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-26-02-0002-0054

- John Laurens to Alexander Hamilton, July 1782, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-03-02-0044

- Alexander Hamilton to John Laurens, 15 August 1782, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-03-02-0058

- Alexander Hamilton to Nathaniel Greene, 12 October 1782, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-03-02-0090

23. Alexander Hamilton, Ron Chernow, 174

NatXx

I came about to read this from reading my book: Red white and royal blue. And without sound rude, coming from someone who is Heterosexual; I didn’t know History was so Queer.