Miss Betty Cooper: Eighteenth Century Drag Queen?

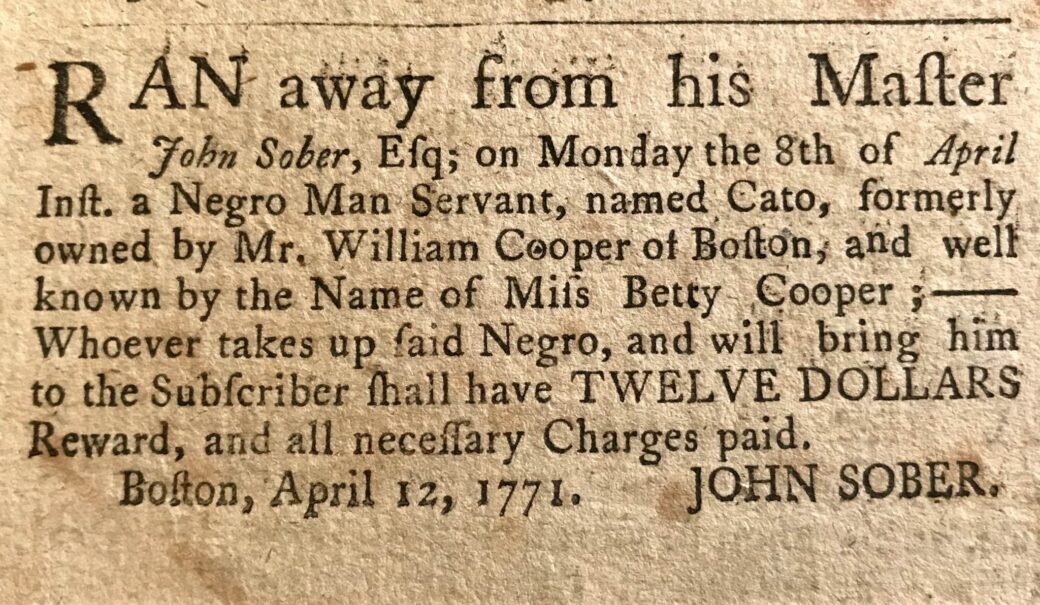

In the April of 1771, an ad seeking the return of a runaway slave ran in Boston’s newspapers. The ad read: “Ran away from his master, John Sober [sic], Esq; on Monday the 8th of April, Inst., a Negro Man Servant, named Cato, formerly owned by Mr. William Cooper of Boston, and well known by the name of Miss Betty Cooper; – Whoever takes up said Negro, and will bring him to the subscriber shall have TWELEVE DOLLARS Reward, and all necessary charges paid.”¹ This ad is unlike most fugitive slave ads in a variety of ways, the most glaring being that John Sober refers to the person he seeks as a man and then mentions that they are well known by a woman’s name. So who is Cato/Miss Betty Cooper? How did she come to be well known by her female name? And what happened to her after she fled slavery?

(Note: In this article I will be referring to my subject as Betty Cooper, and using she/her/hers pronouns. It is unclear if this is what she would have wanted, but since the male name and pronouns in the ad seem to be being imposed on her by her owner, whereas she presumably took a female name on her own, referring to her in this way seems more in line with her own wishes.)

The Ad

The ad John Sober posted is our best insight into Cooper’s life, so it must be examined thoroughly. The first thing it tells us is that Cooper was previously owned by William Cooper. William Cooper spent most of his career as a town clerk in Boston, and was a member of the revolutionary group known as the Sons of Liberty. He seems to have been fairly well known in Boston at the time.² It is interesting that Betty Cooper’s self chosen name includes the last name of an owner. Many slave holder’s did impose their last names on their slaves, so it is possible that Cooper just decided to keep the last name she had been given. It could also have been a way for her to flaunt or expose her true origins if William Cooper was her father. This would make her like George Washington’s enslaved valet, whom Washington said “insists on being called William Lee,” the last name being taken from his previous master whom it was widely rumored was Lee’s father.³

The next thing the ad tells us is that the enslaved person Sober sought was “well known by the name of Miss Betty Cooper.” The significance of Cooper’s chosen first name will be discussed later, but for now it is important we draw attention to “well known by the name.” How did Miss Betty Cooper come to be well known? And well known by a female name? It is of course possible that people around a town could get to know someone else’s slave. In Boston at that time it was common for male (or perceived male) slaves to be hired out to other people or businesses, who would pay rent on the slaves and/or give the owner the slave’s wages.⁴ Additionally, many people might have met Cooper if she often attended William Cooper, who as previously mentioned was a well known man in town. But how, during the course of any of these common activities, would she come to be known by a woman’s name?

The mystery of Cooper’s fame is only compounded when we consider the next clue provided by the ad. As Caitlin G.D Hopkins points out in her article on Betty Cooper, runaway slave ads always included a physical description of the slave; how was anyone supposed to recapture the slave, if they had no idea what the person looked like? And yet Sober’s ad does not include an age, a height, or any details of the clothing Cooper might have run away in. Hopkins suggests that this must mean the people of Boston all knew what Cooper looked like.⁵ Apparently mentioning that this sought after person was Miss Betty Cooper was all Bostonians needed to picture her.

The last few details of the ad include the reward offered, and the name of the man seeking Betty Cooper’s return. The average amount of reward money at that time was about ten dollars, roughly $335 today.⁶ The reward for Betty Cooper was twelve dollars, or about $400. This puts the reward firmly in the range of average for the time. The man offering this reward was John Sober. Sober, originally an Englishman, was the owner of a large plantation owner on the island of Barbados.⁷ Enough of his story is lost that I am not quite sure what he was doing in Boston. What we do know is that he bought Betty Cooper in 1769, just two years before she escaped slavery.⁸ This suggests that if Cooper was famous in Boston, she was likely already becoming so while under the ownership of William Cooper.

So what’s going on here?

I have already discussed the choice of the name Cooper, so let us turn now to the significance of the name Betty. During my research, Hopkins brought to my attention several instances of “Betty” being used as slang to call someone feminine. The first of these was a letter John Adams wrote to his wife. Adams mentions: “I am to dine with Mr. Waldo, to day [sic]. Betty, as you once said.” We do not know in what context Abigail Adams once called Mr. Waldo “Betty.”⁹ It seems likely however that she was accusing him of being feminine. I discussed Abigail Adams’s homophobia/attachment to gender norms in my article about her son, Charles. The idea that “betty” may have meant feminine is bolstered by the another instance Hopkins found, an entry in the Oxford English Dictionary which gives as the definition for “bettying about” as: “to fuss about, like a man who busies himself with a woman’s duties.”¹⁰ In my own research I found a different, though possibly related, meaning for “betty.” In a collection of slang terms which all meant “he’s drunk,” Benjamin Franklin lists “He’s kiss’d black betty.”¹¹ Apparently “black betty” had several meanings at the time, in that case a bottle of whiskey.¹²

“Betty,” it seems, could have meant a general stereotype of femininity or an image of black women somehow connected to a variety of things including alcohol. If Betty Cooper did choose her first name for either of these reasons, it almost seems as though she intended to be a bit humorous, perhaps even entertaining to others. Is it possible Betty Cooper was an early drag queen? Could this be how she was so well known to the people of Boston?

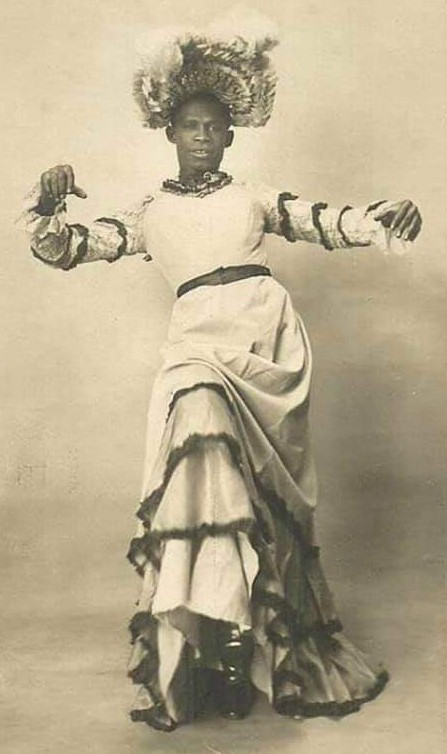

People of color have always played an integral role in the history of drag queens. Historian Dr. Channing Joseph believes that a former slave named William Dorsey Swann was the very first drag queen.¹³ Swann seems to be part of a legacy of black drag queens who crafted an artform that often persuaded white people to journey into centers of black culture. A prime example of this can be found later in history, when Harlem’s drag culture drew an audience diverse in race, gender, and sexuality.¹⁴

At first it sounds unrealistic that an eighteenth century slave holder would have allowed their slave to do something like performing as a drag queen, but slave owners at the time may not have been that invested in policing the gender of their slaves. As Curdella Forbes noted: “Freedom from all social institutions meant freedom from gender, that is, gender was an exclusive category, one of the many signifiers of the slave’s social nullification which was rooted in its/her/his legal status as property or livestock.”¹⁵ Slaves were not part of society, so they were not subject to society’s rules. Slave holders saw enslaved people as livestock, and no one polices their livestock’s gender. There may be some exceptions to this way of thinking; slave owners determined to force Christianity on their slaves, for instance, may have had motivation to regulate gender. And certainly as the nineteenth century got under way, and slaves reproducing became the only way for the institution to continue in the United States, slave holders may have gotten more invested in their slaves’ gender roles in order to ensure they were fulfilling proper sexual roles. In the late seventeen-sixties however, a slave who brazenly defied gender expectations may have been thought very entertaining by whites, even if they did not respect the performer. If white people were amused by Betty Cooper, William Cooper and then John Sober would probably have had few scruples about profiting off it.

What happened to Cato/Betty Cooper?

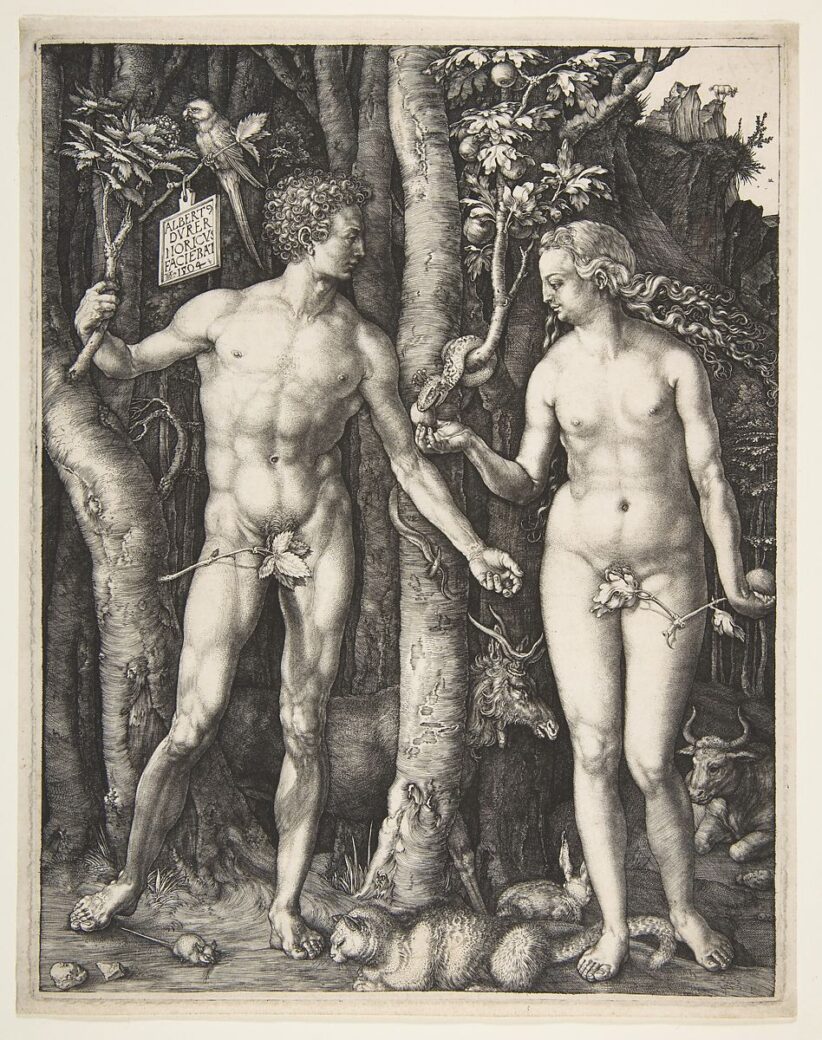

In April of 1771, Betty Cooper left that life behind. But what happened to her after her escape? If she did live the rest of her life free, it is possible Betty Cooper ended up in Savannah, Georgia. In Savannah there lived an Englishman named John Barnard, son of the London mayor of the same name, and he left some record of a Miss Betty Cooper. In a late eighteen hundreds biography of artist Albert Durer, author William B. Scott mentions that John Barnard “was in the habit of inscribing his fine possessions to persons whom he thought worthy of that distinction.” On the back of one of Durer’s works Barnard apparently wrote: “Accomplished Miss Betty Cooper, of St. James’s Street.”¹⁶ Barnard’s inscription appears in several books on Durer’s work, including Catalogue of a Collection of Engravings, Etchings, and Woodcuts, by Richard Fisher. This book mentions the inscription on the back of the work and then explains: “Mr. Barnard, who was a bachelor, lived in St. James’s Square. His near neighbor, Miss Betty Cooper, was a notoriety in his day, and kept a florist’s shop in St. James’s-Street.”¹⁷ But does the second “his” in the phrase “his near neighbor, Miss Betty Cooper, was a notoriety in his day,” refers to Barnard or to Cooper? If it refers to Cooper, then this is evidence of a person named Betty Cooper, living free at roughly the right time, who some people thought should be referred to using he/him pronouns. It may seem counterintuitive at first for an escaped slave to go south, but as Hopkins pointed out to me during my research, there were no free states at that time, and thus there was no clear advantage to going north or south.¹⁸ It may have made more sense in fact for Betty Cooper to go south, as she was more likely to be recognized in Massachusetts and the surrounding colonies. She was apparently well known enough to be recognized on sight without a physical description being provided, after all.

There are some problems with the theory that Miss Betty Cooper ended up in Savannah. First of all, John Barnard of Savannah Georgia was not a bachelor. He came to America with his wife, and if she had died by that point he would likely have been referred to as a widower rather than a bachelor. It is also somewhat unclear if the books referred to St. James’s Street in Savannah Georgia, or St. James’s Street in London England. It seems like a big coincidence that there would be a John Barnard living on St. James’s Street in both America and England, but it is possible. The Barnard in America had emigrated from England, leaving behind a large family of Barnards, and his father was mayor of London.¹⁹ If I am wrong about the location, and the books are talking about a John Barnard and a Miss Betty Cooper in London instead of Georgia, this could still be the Betty Cooper who ranaway from John Sober; perhaps Cooper found a way to join the crowds fleeing to England during the Revolution.

There are a few details that do not fit with this Betty Cooper being the one I am looking for, whether she lived in Savannah or London. First of all, it seems odd that neither book that mentioned Barnard’s friend Cooper mentioned she was black. Both were written in the late eighteen hundreds, when an author would likely have thought they could not describe a person of color without mentioning their race, at least briefly. Then there is a strange detail which one of the books does provide. Both mention that Miss Betty Cooper of St. James’s Street was a florist, but the biography of Durer adds that Cooper was “handsome” (a term which could apply to a man or woman at the time) and “attracted many admirers and much custom to her shop.”²⁰ If the Betty Cooper in question was a person of ambiguous gender (to outsiders at least) then a late nineteenth century writer would probably have been more wary of commenting on her beauty or the fact that she had admirers. Neither of these details proves the Betty Cooper the books talked about was not the one from Boston, but they are worth noting.

The story of Miss Betty Cooper is one that desperately needs to be uncovered. Knowing how Cooper handled living openly as either a non-cisgender person, a drag queen, or both in the late eighteenth century could change the way most people today imagine attitudes about sex, gender and sexuality in that era. Cooper’s story is also valuable for its own sake. Clearly Cooper lived an extraordinary life, and it deserves to be remembered in its full complexity. I plan to revisit Cooper’s story sometime in the future, and I hope other historians will continue to work to help the incredible story of Miss Betty Cooper be remembered.

Sources:

- “Well Known as Miss Betty Cooper”, Caitlin G.D Hopkins, “Well Known as Miss Betty Cooper” – Public Seminar

- Footnotes, Massachusetts Historical Society, 2, and “William Cooper, Jr., Captain’s Clerk, Chaplain, 2nd Lieutentant of Marines”, William Cooper, Jr., Captain’s Clerk, Chaplain, 2nd Lieutentant of Marines | Continental Navy (an article about his son that also gives some information on William Cooper Sr.)

- “William (Billy) Lee”, William (Billy) Lee · George Washington’s Mount Vernon

- “The Negro at the Gate: Enslaved Labor in 18th Century Boston”, Jared Ross Hardesty, “The Negro at the Gate”: Enslaved Labor in Eighteenth-Century Boston on JSTOR

- See #1

- To see the data I used to calculate the average amount of reward money, see: Freedom on the Move, for my inflation calculations see: $12 in 1771 → 2021 | Inflation Calculator (officialdata.org)

- See #1, and “John Sober II”, Summary of Individual | Legacies of British Slave-ownership (ucl.ac.uk)

- See #1

- Caitlin G DeAngelis on Twitter: “@Boston1775 @18thPride I have definitely wondered whether Miss Betty Cooper’s name has implications that would have had meaning for an 18thc audience. There’s that cryptic reference to “Betty” in John Adams’ letter re: Francis Waldo (of the “irregular life”). https://t.co/FuHKB7I3hx” / Twitter, The letter she refers to: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/04-01-02-0088

- “Betty, verb”, Oxford English Dictionary

- “The Drinker’s Dictionary, 13 January 1737”, Benjamin Franklin, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-02-02-0029

- “Black Betty by Ram Jam”, “Black Betty” by Ram Jam – Song Meanings and Facts

- “The Former Slave Who Became The World’s First Drag Queen”, https://youtu.be/iT15sCRHKJU

- ““Spectacles in Color”: The Primitive Drag of Langston Hughes”, “Spectacles in Color”: The Primitive Drag of Langston Hughes from Queer Natures, Queer Mythologies on JSTOR

- “TROPES OF THE CARNIVALESQUE: HERMAPHRODITIC GENDER AS IDENTITY IN SLAVE SOCIETY AND IN WEST INDIAN FICTIONS”, Curdella Forbes, https://www.jstor.org/stable/23019789

- Albert Durer: his life and works. Including autobiographical papers and complete catalogues, William B. Scott, 348, #348 – Albert Durer: his life and works. Including autobiographical … – Full View | HathiTrust Digital Library | HathiTrust Digital Library

- Catalogue of a collection of engravings, etchings, and woodcuts, Richard Fisher, 190, #190 – Catalogue of a collection of engravings, etchings, and woodcuts. … – Full View | HathiTrust Digital Library | HathiTrust Digital Library

- Caitlin G DeAngelis on Twitter: “@18thPride Someone with a relative there might. And lots of enslaved people ran toward Florida. Or maybe she got work on a ship and ended up in Savannah that way. That doesn’t mean it is her, but don’t rule it out!” / Twitter

- “Re: John Barnard Will”, Re: John Barnard will – Genealogy.com

- See #16

Anx

Ooh! Can you maybe do an article on William Dorsey Swann? Of course, you don’t have to, but I think it would be cool!