The Story of Celeste

In the summer of 1803, Aaron Burr began writing to his daughter Theodosia about a new courtship he was embarking on. Referring to the woman he pursued only as “Celeste”, Burr explained how he followed the proper steps to begin a formal courtship, how he declared his intentions to Celeste, and how she rejected him by telling him she was determined never to marry. As the story unfolds, some interesting questions are raised. Is it possible that Celeste was either a lesbian, aromantic, or asexual? And what does her story reveal about the realities of eighteenth life for women who were not interested in men?

Burr’s Story

In his letters of June, 1803, Burr begins the story of a very traditional courtship. On the fifth Burr has dinner with Celeste’s family. Burr mentions to Theodosia that he was initially unable to tell which of the sisters was the “imorata,” which is interesting. Nowhere in his previous letters (of those that survive, anyway) does Burr mention how this all got started, but it seems like someone informed him that one of the daughters was available and perhaps interested in him.¹ Burr apparently figures it out, because on the sixth he goes to their house to see Celeste. He talks with her briefly, and arranges to see her father later that day. When the two men meet, Burr formally asks permission to court Celeste and her father grants it.² On the seventh Burr once again goes to see Celeste. They are alone together, and they talk for some time. According to Burr: “For some minutes she led the conversation, and did it with grace and sprightliness, and with admirable good sense. I made several attempts to divert it to other subjects- subjects which might have nearer affinity, again, to others; unsuccessfully, however; yet, whether I was foiled through art or accident, I could not discover.”³

This does not sound like a promising start, but it is nevertheless jarring to read in Burr’s very next letter to his daughter “I told you the negotiation should not be long. It is finished -concluded- for ever abandoned.” Burr goes on to explain: “Celeste means never to marry; “firmly resolved.” I am sorry to hear it, madam; had promised myself great happiness, but cannot blame your determination. “No, sir, you cannot; for I recollect to have heard you express great surprise that any woman would marry, &c., and you gave such reasons, with so much eloquence, as made an indelible impression on my mind.””⁴ Obviously it was shocking for a woman in that era to declare she is never going to get married. The reason she gives is that Burr had previously convinced her it is a mistake for any woman to get married. But was Celeste telling the truth? Did she really decide never to marry, and was it really because Burr had convinced her that it was not in her best interest as a woman to do so? Theodosia questioned Celeste’s resolve, and asked her father, “Do you think this courage will last, or is only a spasm?”⁵ In his letter of the eleventh, Burr updates Theodosia on a new development. The day before Burr had received a formal letter from Celeste asking him not to continue pursuing her. Later that same day, Celeste invited him to her house. “After a pause and several efforts,” Burr tells his daughter, “she, with some trepidation, said that she feared the letter which she had written had not been expressed in terms sufficiently polite and respectful; she wished an opportunity to apologize; and here she stuck…Celeste was profoundly occupied in tearing up some roses which she held in her hand, and Reuben [the fake name he had assigned himself] was equally industrious in twirling his hat, and pinching some new corners and angles in the brim.” Burr assumes she is trying to take back her rejection of him, and says he will start pursuing him again; she tells him not to. Burr admits to Theodosia in his letter that he may have been wrong, and then that Celeste may not have been trying to take back her rejection, just to apologize in case her rejection came across as rude.⁶ The next day he goes to see Celeste again, and tells her that he now understands what she was trying to say. Burr notes that ““During the interview, Celeste, having no roses to occupy her hands, twisted off two corners of a pocket handkerchief.”⁷

In Theodosia’s next letter she gives her thoughts on the string of events, from rejection letter to apology. She believes that Celeste was in fact playing hard to get, and that when Celeste summoned Burr to her house to apologize Burr was supposed to begin a valiant fight for her love.⁸ Whether Burr agrees or disagrees with this advice, he does not mention Celeste again until the following February.

Burr encounters Celeste on the twenty-first, and decides it is a good time to renew his attempts to propose marriage. Burr relates to Theodosia that “It excited an agitation perfectly astonishing. The emotion was so great as to produce universal tremour, which attracted the notice of the company (there was a room full); I was exceedingly alarmed and perplexed.” Upon receiving a second marriage proposal from Burr, Celeste seems to have had something akin to a panic attack. Could Celeste have simply been experiencing anxiety caused by the pressure to get married? Celeste claimed to be morally opposed to marriage, and yet her father was apparently meeting with suitors and giving them his blessing to pursue her; this had to have been a stressful time for Celeste. But could there be a different reason? Burr thinks there is something going on with Celeste which he is unaware of. Mulling to Theodosia, Burr remarks: “Undoubtedly there is some secret agent, some underwork, perhaps restrain, of which I am ignorant. I strongly suspect that she has done violence to her feelings.”⁹

Burr mentions a week later that Celeste is mailing him a copy of a speech that he needs, so apparently they stayed in contact. He does mention that he has not been to see Celeste lately though, as he is offended by the way she behaved the last time they met.¹⁰ Burr does not mention Celeste in his letters again until the following August, by which time he had killed Alexander Hamilton. On the second, mere weeks after the disastrous duel, Burr updates Theodosia on his latest attempts to get Celeste to marry him, telling her “Nothing can be done with Celeste. There is a strange indecision and timidity which I cannot fathom.”¹¹ Burr does not seem to have taken much heed of the reasons Celeste gave for not wanting to marry him; instead he describes, as in his letter of February twenty-first, a strange inner conflict he senses in Celeste which keeps her from expressing her true feelings.

Burr mentions Celeste again a week later. This time he believes she seems more open, and he thinks he could have success with her, if only he were not forced to travel to the nation’s capital in order to perform his final duties as vice president.¹² Burr does not see Celeste again for months, but in January he writes to his daughter with a dramatic confession: he is traveling to Philadelphia for the sole purpose of finally winning Celeste’s love.¹³

This is a bit surprising, as it is the first hint we get that Burr may actually have been in love with Celeste. The feeling was not returned, however. In his very next letter Burr tells Theodosia: “The affair of Celeste is for ever closed, so there is one trouble off hand.”¹⁴ Though Burr mentions Celeste one more time in March, commenting that she is trying hard to continue looking young and that she was flattering towards him, Burr finally abandons his attempts to make Celeste his wife.¹⁵

What does it all mean?

I first encountered this story while researching Aaron Burr, and I was struck by both the uniqueness of Celeste’s determination never to marry, as well as the sheer amount of panic Burr’s advances seemed to cause for her. Did Celeste truly believe women should not marry? Did she panic when Burr proposed repeatedly because she was under tremendous pressure to find a husband? Or could her opposition to marriage and panic at Burr’s proposals be because she was not attracted to men?

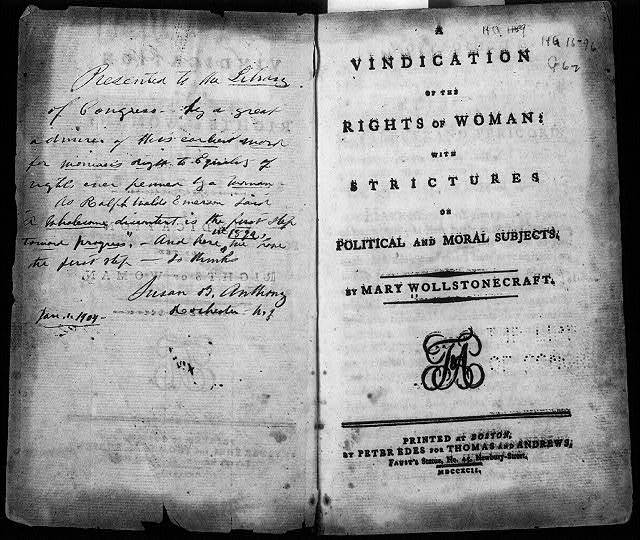

The reason Celeste gave for not wanting to marry was that Burr had convinced her marriage was never a good idea for a woman, but this reason may not hold up under scrutiny. Burr’s favorite Feminist writer, Mary Wollstonecraft, was not opposed to marriage; she believed there was nothing wrong with marriage if the two people were real friends, and if they were equals in the partnership.¹⁶ It is hard to imagine what Burr might have said to convince Celeste that in marrying she would give up any power or rights that she had. It is true that marriage meant losing certain property and other legal rights at the time; in her current state however, Celeste was entirely dependent on her parents.¹⁷ Unmarried, she would essentially be treated as a perpetual child, unless she had some sort of plan to go off on her own. The sexist systems in place at the time meant that Celeste lacked autonomy whether she stayed at home with her parents or became Burr’s wife. Even if there is a very convincing argument Burr could have made for why women should not marry, he does not seem to have recalled making one. Burr was completely surprised to hear Celeste say that he had persuaded her never to marry.

Could Celeste’s actions be better explained by the theory that she was not attracted to men? There does seem to be some evidence for this theory. Celeste’s pattern of enjoying Burr’s company until he tries to make things romantic, and then having anxiety or panic attacks, seems highly reminiscent of the horror experienced by many lesbian, aromantic, and asexual women when they realize their male friend is becoming insistent upon a romantic and sexual relationship. And then there is Burr’s claim that Celeste had “done violence to her feelings.” Burr believes that Celeste is emotionally tormenting herself, that she wants to let her heart go in a certain direction but that she is holding herself back. And yet, Celeste’s rejections of Burr do not really seem like veiled attempts to get him to fight through her defenses. Celeste repeatedly rejects him, stumbling in her determination only when she is worried that she has offended him. It seems like her desires not to marry and not to have a relationship with Burr were genuine. If she was holding herself back then, it was not from Burr, or from marriage in general, neither of which she felt any draw towards. Where was her heart leading her that Celeste refused to go?

Who was Celeste?

Burr biographer Nancy Isenberg claims in her book Fallen Founder that “Celeste” was not this woman’s real name, and Isenberg is most likely correct.¹⁸ Burr often assigned fake names to the people he had romances with, in an effort to protect their privacy should the letters fall into the wrong hands. Burr actually renamed himself in many of his romantic correspondence and tales as well, as in this case where he refers to himself as “Reuben.”¹⁹ So who was Celeste really?

Isenberg believes we will never know for sure who Celeste was. This may not be true, but it is certainly a mystery for now. There are however, certain things which we can know about Celeste, and some which we may make educated guesses on, based on things Burr says in his letters. We can guess that Celeste was a young woman, perhaps in her twenties, in 1803. According to Nancy Isenberg, Burr preferred younger women, and he would likely have mentioned her age to Theodosia if Celeste was an exception to this. We also know she had sisters, and can guess she was the oldest. Burr mentions her family owning several slaves, which also means they must have been wealthy. We know her family lived in Philadelphia most of the time from at least 1803 to at least 1805. It is likely her father was not politically devoted to Thomas Jefferson or Alexander Hamilton, or else he would probably not have encouraged Aaron Burr to pursue one of his daughters in 1803. Celeste herself was probably not particularly attached to at least Hamilton, as her friendship with Burr survived him killing Hamilton. This last point is a bit shaky though, since, as I discussed in my article on Robert Troup, reactions to Hamilton’s death were not always what we would expect.²⁰

These details paint a vague portrait, as there must be many women to whom they could apply. I include them here though because they do give us some context for Celeste’s experiences, and in hopes that someone who reads this may eventually stumble upon Celeste’s true identity.

There definitely is some evidence that Celeste was either a lesbian, asexual, or aromantic. It is significant that Celeste did not just reject Burr, but vowed never to marry; marriage was expected of everyone at the time, and few people would have thought to challenge that rigidly enforced societal mandate. Though Celeste gives a reason, her explanation does not make complete sense, particularly since she would have been just as deprived of rights living with her natal family as she would have been with a husband. Celeste also seemed to experience much more anxiety around the topic of marriage than one would expect. In many of their meetings she seemed very upset, destroying small things in her hands or having full blown panic attacks. Though it is hard to say for sure, this behavior seems highly reminiscent of someone trying to fend off advances from someone they are not attracted to without outing themselves. Then there is Burr’s point about the resistance he senses in Celeste. In Burr’s vanity and mild sexism he assumes Celeste wants him but is unwilling for some reason to say so, and that her attempts to reject him are just part of the game. To an outside viewer however, Celeste’s rejections seem pretty real; what then was the cause of her inner turmoil?

There are many reasons then to suspect Celeste was a lesbian, asexual, or aromantic, but without further evidence most of these arguments rest to some degree on speculation. Most likely we will not know for sure what Celeste’s orientation was until we actually find out who she was and are able to study her life more deeply than the letters of one would-be-suitor allow.

What little we do know of Celeste’s story does have merit for our studies of LGBT+ history though, as it opens a window to the possible experience for all wealthy and urban lesbian, asexual, and aromantic women of the time. Like Celeste, these women were all expected to marry; they all received unwanted marriage proposals; and they all had to deal with the occasional male friend who wanted their friendship to become something else. Like Celeste, they would have had to either accept an unpleasant (or at least unfulfilling) marriage or come up with a reason why they could never marry. They then had to find a way to deal with either the wrath of a rejected lover or the persistence of men who, like Burr, refused to get the message. Living in a society governed by sexist and heteronormative systems, these women had to learn to slip through the cracks.

Sources

- Aaron Burr to Theodosia Alston, 5 June 1803, Correspondence of Aaron Burr and his Daughter Theodosia, edit by Marc Van Doren (all letters cited below were also found in this book unless otherwise specified)

- Burr to Alston, 6 June 1803

- Burr to Alston, 7 June 1803

- Burr to Alston, 8 June 1803

- Alston to Burr, 9 June 1803

- Burr to Alston, 11 June 1803

- Burr to Alston, 12 June 1803

- Alston to Burr, 14 June 1803

- Burr to Alston, 21 February 1804

- Burr to Alston, 28 February 1804

- Burr to Alston, 2 August 1804

- Burr to Alston, 11 August 1804

- Burr to Alston, 15 January 1805

- Burr to Alston, 28 January 1805

- Burr to Alston, 29 March, 1805

- “Back to the Future: Marriage as Friendship in the Thought of Mary Wollstonecraft”, Ruth Abbey, Back to the Future: Marriage as Friendship in the Thought of Mary Wollstonecraft on JSTOR

- “A Short History of Women’s Property Rights in the United States”, Jone Johnson Lewis, A Brief History of Women’s Property Rights in the U.S. (thoughtco.com)

- Fallen Founder, Nancy Isenberg, 237-239

- Another example of Burr renaming his lover and himself in correspondence: Burr to Alston, 10 July, 1804

20. “The Three Loves of Robert Troup”, Megan Gackler, The Three Loves of Robert Troup – 18th Century Pride