The Court Martial of Friederick Gotthold Enslin

In the spring of 1778, a scandal began in the Continental Army which would end with Lieutenant Friederick Gotthold Enslin dishonorably discharged from the for almost having sex with Private John Manhart (sometimes spelled “Monhort”) and for perjury. Enslin’s case is the first of only two sodomy cases historians currently know for sure happened in the Continental Army. Because of this, Enslin’s case is used to make all kinds of statements about how same-sex relations were viewed and handled by the Continental Army. But what can Enslin’s case actually teach us, and what does it leave us to guess about?

Enslin

Based on records of loyalty oaths administered in Pennsylvania, Friederick Gotthold Enslin arrived in the colony on September 30th, 1774, on the ship Union. He apparently came from Rotterdam.¹ According to LGBT+ historian Randy Shilts’s book Conduct Unbecoming, Enslin was in his late twenties to early thirties. Shilts also proposes that Enslin was educated and wealthy, based on his penmanship, his impressive grasp of English, and the fact that when Enslin joined the Army he quickly became an officer, in Colonel William Malcolm’s Additional Regiment.²

Maxwell’s Court Martial

This story starts with the court martial of a different man, Ensign Anthony Maxwell, also of Colonel Malcolm’s Additional Regiment. Sometime in February of 1778 Major Aaron Burr, temporarily in charge of the regiment while Malcolm was away, became aware of Maxwell saying he had caught Enslin in a compromising position with Private John Manhart.³ It is unclear if Burr heard this directly from Maxwell, or if he caught wind of a rumor Maxwell had started. Maxwell would later be referred to as “propagating [spreading] a scandalous report” which may mean it was the latter, although perhaps Burr saw Maxwell just telling him as an attempt to spread a rumor.

Either way, Burr ordered Maxwell to be given a court martial for slandering Enslin, Maxwell’s commanding officer. This was an era in which honor culture had a strong hold on men of the gentlemanly class. Maxwell saying something like this about an officer was a grave offense.

Maxwell appeared before the court martial on February 27th. During this court martial, Enslin testified that what Maxwell had said was completely false. Evidently, however, Maxwell convinced them he was telling the truth. According to the General Orders for March 3rd, “The Court after maturely deliberating upon the Evidence produced could not find that Ensign Maxwell had published any report prejudicial to the Character of Lieutt Enslin further than the strict line of his duty required.”⁴ In other words, Maxwell had done nothing more than report a crime. Interestingly, Maxwell’s later promotion to second lieutenant would be backdated to the day after his acquittal, though it is unclear if this is a coincidence or a reward for his actions.⁵ Later I will discuss the debate on whether what happened between Enslin and Manhart was consensual sex or rape; it is unclear, if Maxwell’s promotion was a reward for reporting Enslin, whether he was being rewarded for reporting rape or for outing Enslin.

Enslin’s Court Martial

Not long after Maxwell was aquitted, Enslin was put on trial for attempted sodomy and perjury. When modern reads hear “attempted sodomy” (emphasis added) they often assume this means that Maxwell saw Manhart fighting Enslin off, and that what happened between Enslin and Manhart was rape. While the interaction may not have been consensual (a possibility which will be discussed in full later) that is not what “attempted sodomy” means. In Arthur N. Gilbert’s essay “Buggery and the British Navy” he explains that, in contrast to crimes like murder, where the line between attempting and fully committing the crime is clear, the line between sodomy and attempted sodomy had to be pinpointed in the law. The British Navy used penetration as the standard for when attempted sodomy became sodomy. Obviously in most cases it was impossible to know if penetration had actually occurred, even if another sailor caught his comrades in the act. In most cases it seems to have come down to whether the officers conducting the court martial wanted to put the sailor to death or not, since the punishment for sodomy was always death whereas the punishment for attempted sodomy could be a number of things. Officers who felt bad condemning a fellow soldier to death might claim the evidence of penetration was insufficient, even if the same amount of evidence had sufficed in other cases. Officers particularly horrified by same-sex relations, on the other hand, or who perhaps felt that what the accused had done was actually pedophelia and/or rape, might accept whatever evidence had been presented because he felt the sailor needed to be put to death.⁶

Many American states were still using English Common Law at the time (and in fact many would continue to do so for years after the war) which said that the standard for sodomy was emission (ejaculation), so this may be what the Continental Army used.⁷ Whichever standard was in use, things likely played out in the Continental Army just as they did in the British Navy; it was impossible to know for sure if sodomy had been fully comitted, so whether a soldier was convicted of sodomy or attempted sodomy came down to whether those conducting the court martial felt the soldier deserved death. Evidently, the officers sitting on Enslin’s court martial did not believe he did.

Enslin’s Discharge

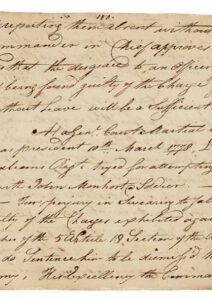

The General Orders for March 14th, 1778, declared:

“At a General Court Martial whereof Coll Tupper was President (10th March 1778) Lieutt Enslin of Coll Malcom’s Regiment tried for attempting to commit sodomy [sic], with John Monhort a soldier; Secondly, For Perjury in swearing to false Accounts, found guilty of the charges exhibited against him, being breaches of 5th Article 18th Section of the Articles of War and do sentence him to be dismiss’d the service with Infamy—His Excellency the Commander in Chief approves the sentence and with Abhorrence & Detestation of such Infamous Crimes orders Lieutt Enslin to be drummed out of Camp tomorrow morning by all the Drummers and Fifers in the Army never to return; The Drummers and Fifers to attend on the Grand Parade at Guard mounting for that Purpose.”⁸

Washington’s addition to Enslin’s sentence is worth noting. As John B.B Trussel Jr. says in his book Birthplace of an army: a study of the Valley Forge encampment, Washington adding to sentences did not fall within Washington’s job description.⁹ James C. Neagles explains in his book Summer Soldiers: A Survey and Index of Revolutionary War Courts Martial that as Commander in Chief, Washington was supposed to review all sentences handed down in the units he commanded. He could say yes or no to a proposed sentence, or he could lessen the punishment or completely pardon the offender. There were a number of occasions on which Washington said no to a punishment because he felt it was not strict enough. There does not seem to be any case besides Enslin’s, however, in which Washington added to it as he does here.¹⁰ Washington made Enslin’s discharge a spectacle, and in so doing ensured that everyone in the Army would remember Enslin if Enslin ever tried to reenlist.

The ceremony was carried out as Washington ordered. The diaries and journals of several soldiers who were at camp at the time described the drumming out, including that of Lieutenant James McMichael. According to McMichael:

“I this morning proceeded to the grand parade, where I was a spectator to the drumming out of Lieut. Enslin of Col. Malcolm’s regiment. He was first drum’d from right to left of the parade, thence to the left wing of the army; from that to the centre, and lastly transported over the Schuylkill with orders never to be seen in Camp in the future. This shocking scene was performed by all the drums and fifies in the army -the coat of the delinquent was turned wrong side out.”¹¹

What happened to Enslin after this is unknown, although a Boston Directory from 1798 lists a “Enslin Gotthold F.” living on Newbury Street.¹²

Washington’s “abhorrence and destestation of such infamous crimes,” is also interesting. It has been suggested that this could refer to the perjury charge. Certainly this charge should not be seen as something small and technical tacked on to the larger crime of sodomy. As I said above, men in late eighteenth century America existed within Honor Culture; a man’s good reputation was a currency which he had to use to get anything in life. On a more practical level, perjury made it impossible to enforce discipline. An ensign named Cocke was discharged for lying about the behavior of an officer, almost the exact same thing Enslin had done.¹³ Clearly Enslin’s lie about Maxwell was no small thing. It still seems likely, however, that Washington’s horror was over the sodomy charge. The part of the Articles of War Washington cites in his orders covers general disorderly behavior, and seems to have been the article under which Enslin was punished for sodomy, rather the one under which he was punished for perjury.¹⁴ The question then becomes, was Washington disgusted by consensual sex between men or rape?

Was it consensual?

Whether two men were caught having consensual sex in a private place or a man was caught brutally raping another man, the eighteenth century labeled it sodomy. This makes it hard to determine the nature of a situation simply from a charge that says “attempted sodomy.” There are some elements of this story however which suggest that Enslin’s sexual interaction with Manhart was not consensual.

From what I could find, there is no evidence of Manhart ever being given a court martial. His name does not appear in Neagles’ list of the 3,315 courts martial conducted by the Continental Army.¹⁵ We know he was not discharged as a result of the incident, because we have records of his continued service. Manhart remained part of Malcolm’s Additional Regiment as the regiment merged with Col. Oliver Spencer’s, and in May 1779 he became a corporal. He left the Army in 1780.¹⁶ That Manhart was promoted is especially telling, as it seems likely that if he had been convicted of anything related to sodomy, even a lesser crime than the one Enslin was convicted of, it might have hurt his chances for advancement. So why did Manhart get out of the scandal with his reputation in tact, while Enslin was discharged for attempting sodomy with him? One possible explanation is that he was determined to be a victim of rape. In the eighteenth century British Navy there were instances of one partner not being charged if he reported the incident, and reported it as rape.¹⁷ Though Manhart was not the one who reported what happened with him and Enslin, he may still have testified that he was raped at Enslin’s court martial. It is also possible that military commanders at the time had at least some understanding of the unequal power balance between Enslin and Manhart. Enslin was at least a little older than Manhart, who was about eighteen.¹⁸ Enslin was also an officer in Manhart’s regiment, and one of Mahart’s commanders. These facts create obvious potential for sexual coercion. Enslin could have threatened to punish Manhart or to put him in harm’s way in battle. He could also have made rewards like promotion contingent on Manhart having sex with him.

With the evidence we currently have it is impossible to say exactly what happened between the two men, or to what extent Manhart may have wanted to have sex with Enslin. Still, we can see that the relationship was at best inappropriate.

What does it all mean?

When courts martial for sodomy in the Continental Army are brought up as part of LGBT+ history, someone always mentions that there were only two such cases, that of Lt. Enslin and that of a John Anderson who was found “not guilty of sodomy but guilty of attempted sodomy,” and was beaten.¹⁹ However, this number may not be completely accurate. In his book Male-Male Intimacies in Early America, historian William E. Benemann proposes that there may have actually been many more courts martial for sodomy. Benemann suggests that if a commander did not want to bring shame and embarrassment upon their unit, or perhaps upon the accused, they may have made sure that the records of the court martial were vague enough that no one outside the unit would be able to tell what had happened. According to Benemann this may have been done by using purposely vague language, such as “conduct unbecoming of an officer and a gentleman.”²⁰ In Neagles’ index of all the Continental Army’s courts martial, there are seventeen instances where the crime is recorded as some variation either of “conduct unbecoming” or “scandalous behavior,” and twenty-one where no crime is listed at all.²¹ These instances of vague records are particularly interesting because other Continental Army court martial records are very detailed, even when they discuss sexual transgressions involving women.²²

Gilbert agrees with Benemann that there were typically more cases of sodomy in a military of that era than we have record of, and suggests there were probably many cases that never even made it to a court martial. In his essay on the British Navy, Gilbert notes that commanders may have looked the other way, or fellow sailors may not have reported things they witnessed, out of pity for guilty comrades they knew would be put to death if charged with sodomy. Gilbert also suggests that for this reason some commanders may have punished the guilty on their own without ever having them appear before a court martial and be formally charged.²³ Since the Continental Army also followed English Common Law and thus also had the death penalty for sodomy, the same practices may have occured.

Enslin’s case may have been one of sexual assault, and Benemann believes Anderson’s may have been as well.²⁴ The fact that both of the known cases may have been sexual assault has often been used to draw the conclusion that the Continental Army was actually accepting of same-sex relations, and horrified only by rape. We cannot actually draw this conclusion; sodomy cases that are actually rape will always be more prevelant in court records than consensual sex. When two men snuck off together for consensual, private sex, there was no one to report the crime, or evidence of it having been comitted, unless they were caught. This does not mean the Army would not have punished men for consensual male-male sex if they had caught them, only that catching those who engaged in consensual sex was much harder to do. What might have happened had two men caught engaging in clearly consensual sex is at this point unknown.

The court martial of Frederick Gotthold Enslin for attempted sodomy and perjury is always brought up when anyone talks about the LGBT+ experience in the eighteenth century because it is the closest thing we have at this point to an account of life in the Continental Army for an LGBT+ person. However, as we have seen, Enslin’s story may not be representative of the average same-gender attracted man in the army. Though there remains much uncertainty, Enslin may have been an unscrupulous character who tried to use his power as an officer to force John Manhart to have sex with him.

Because what happened between Enslin and Manhart may have been sexual assault, it is debatable if the extreme reaction to it is representative of feelings about same-sex relations on behalf of the Army or George Washington. Even if we could know for sure that what happened was rape, we do not know if they saw it that way. Furthermore, even if there was evidence that Washington knew Enslin coerced Manhart, it would still be unclear if he was more horrified by the fact that a soldier was forced into sex or the fact that the soldier was forced into sex by another man, or if perhaps a combination of the two.

More research clearly needs to be done into Enslin’s case, but that is not all. In order to form a truly clear picture of how the Continental Army handled sodomy cases, John Anderson’s case needs to be investigated along with all seventeen of those cases that referred vaguely to “conduct unbecoming” or “scandolous behavior,” and possibly the twenty-one that did not list a crime as well. As long as we continue to let one case define our entire perception of sodomy cases in the Continental Army, we will always be using a lot of extrapolation and messy guesses in place of the truth.

- Pennsylvania Archives, Catalog Record: Pennsylvania archives | HathiTrust Digital Library

- Conduct Unbecoming: Gays and Lesbians in the US Military, Shilts, 11, Conduct Unbecoming – Google Books

- General Orders, 3 March 1778, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-14-02-0029

- Ibid.

- Annotations of General Orders for 3 March 1778, University of Virginia, 2

- History of Homosexuality in Europe and America, edited with introductions by Wayne R. Dynes and Stephen Donaldson: Buggery and the British Navy (by Arthur N. Gilbert), 133-135

- Ibid., 133 and Virginia (glapn.org)

- General Orders, 14 March 1778, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-14-02-0138

- Birthplace of an Army: A Study of the Valley Forge Encampment, John B.B Trussel Jr., 84, #84 – Birthplace of an army : a study of the Valley Forge encampment … – Full View | HathiTrust Digital Library | HathiTrust Digital Library

- Summer Soldiers: A Survey and Index of Revolutionary War Courts Martial, James C. Neagles, 6

- “The James McMichael Journal, December 29, 1777-May 12, 1778, Transcribed by Joseph Lee Boyle, The James McMichael Journal, December 29, 1777–May 12, 1778 – Journal of the American Revolution (allthingsliberty.com)

- The Boston Directory 1798, #52 – The Boston directory. 1798. – Full View | HathiTrust Digital Library | HathiTrust Digital Library

- Neagles, 106

- Annotations of General Orders for 14 March 1778, University of Virginia, 3

- Neagles

- See #14

- Gilbert

- See #14

- Neagles, 72

- Male-Male Intimacies in Early America, William Benemann, 73, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Male_male_Intimacy_in_Early_America/q7TPqeUa9UIC?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=Frederick+Gotthold+Enslin&pg=PA71&printsec=frontcover

- Neagles

- Benemann, 75

- Gilbert, 132

- See #20